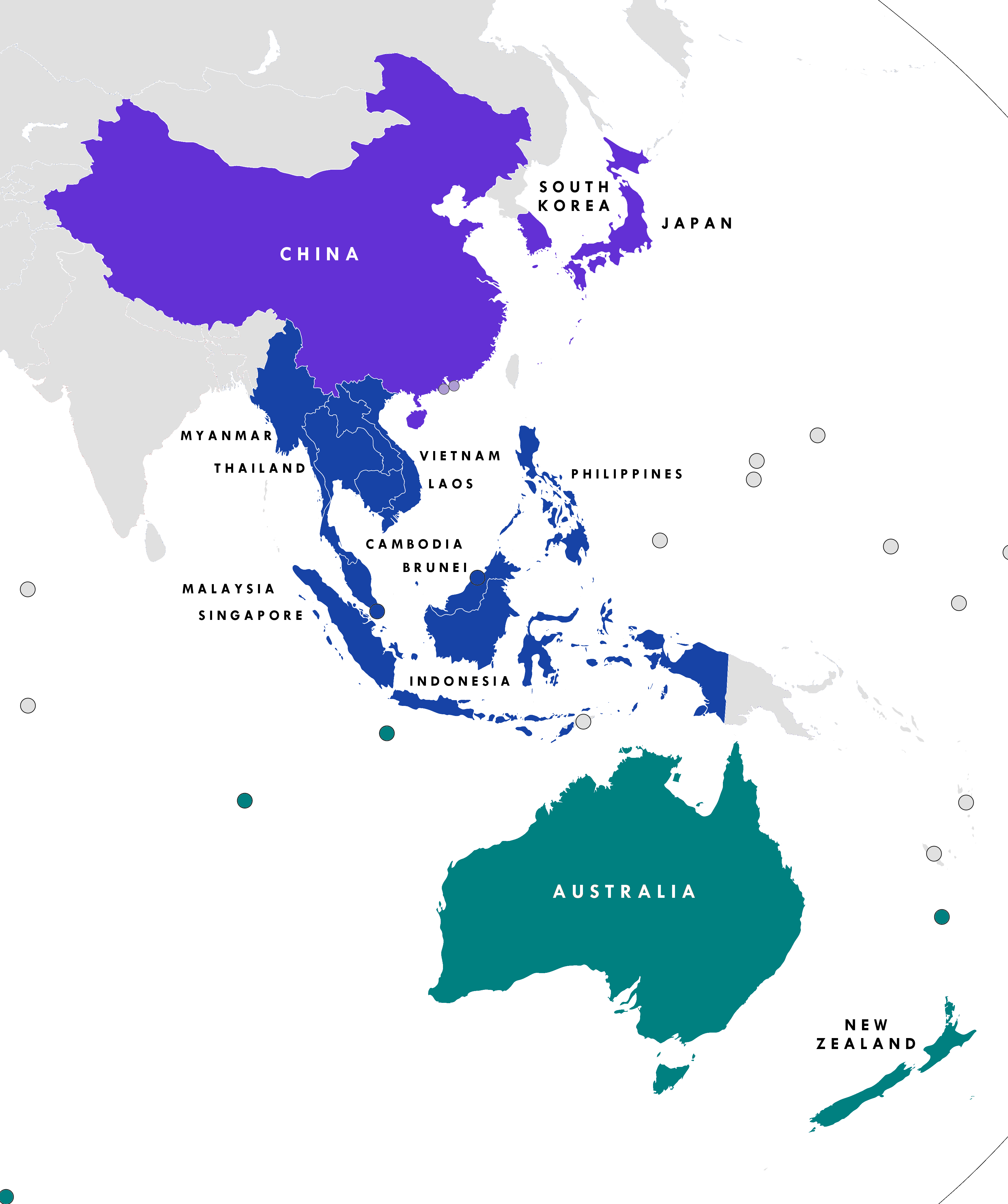

Following eight years of laborious negotiation, Ministers from 15 Asia-Pacific countries inked the newest and biggest trade deal in the world on 15 November 2020. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is expected to be rectified and enacted in early 2021, will comprise a bloc of countries (see Exhibit 1) that make up almost 30% of world population (2.2 billion people) and GDP (USD26.2 trillion), and 28% of global trade.[1]

Negotiations started in late 2012 between the 10 members of ASEAN and its six free trade agreement (FTA) partners, i.e. Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.[2] The negotiators have set an ambitious target to develop a mega trade deal that covers “trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement and other issues”.[3] In particular, the signing of the RCEP Agreement is immensely significant in reiterating the region’s support for “an open, inclusive, rules-based trade and investment arrangement”.[4]

Exhibit 1: The members of RCEP

redit: Wikipedia Commons

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Database Oct 2020.

A mega trade deal – what does it mean to Asia?

Above all, RCEP helps to consolidate many existing FTAs among its signatories. Some 83% of trade among RCEP members are already covered by pre-existing FTAs,[5] including those among the 10 ASEAN members and through various ASEAN+1 Agreements. But significantly no such prior agreements exist between China and Japan, or South Korea and Japan – this will probably generate some of the biggest gains in regional trade and investment going forward. A single overarching FTA also helps businesses to better navigate the different custom areas, for instance, in conforming to the rule of origin requirements which is a prerequisite to qualifying preferential tariff treatment.

The outcome and unfolding of benefits will hinge heavily on commitments and execution, though already it is possible to provide a first glimpse of potential opportunities.

- The bloc aims to lower tariffs and enhance rule-based trading arrangements. While existing FTAs already lowered mutual tariffs to low levels,[6] RCEP can help to reduce complexity (arising from multiple FTAs among original members and groups)[7] and encourage the setup of regional supply chain among member countries.

- RCEP offers a platform for tackling non-tariff barriers (NTBs), which is likely to be more relevant to future global trade governance, given that tariffs have been lowered significantly over the past decades.

- Including rules on intellectual properties and e-commerce will also help to foster stronger regional growth in digital and online transactions.

- New market access commitments for service suppliers and investors in China and ASEAN will enable market liberalisation in those countries.

RCEP also has limitations. These include, for instance, that it is shallower than other major trade deals[8], some commitments are non-bidding and that implementation sometimes takes a long timeframe of up to 20 years. The lack of a strong dispute-resolve mechanism and the complicated tariff schedules are also commonly identified shortcomings. To a large extent, this reflects the different levels of economic development of the participating countries, which necessitates in some cases a longer timeframe to complete custom reforms or reduce tariffs. The aim to maintain open accession to RCEP also warrants more flexibility.

Sizing the insurance opportunity

Notwithstanding its limitations, RCEP is poised to become a major driver of regional economic growth and development in the coming decades. Near-term, it could be instrumental in supporting the region’s response to the pandemic and in ensuring the rebuilding of resilience through inclusive and sustainable economic recovery. Whenever it’s good news to the economy, it’s good news to insurance.

First, trade agreements can foster market liberalisation and deregulation. This is illustrated, for instance, in the ASEAN Insurance Integration Framework under the AEC Blueprint 2025.[9] In this regard, some RCEP members have committed to further liberalisation of their market access regimes. China has earlier made unilateral liberalisation in financial services including insurance, which will be reflected in the country’s commitment to RCEP.[10] Laos, Myanmar and the Philippines will make services and investment commitments on financing services including insurance.

Second, trade deals can include standardisation and harmonisation of rules and regulations, including those governing insurance activities. Mutual recognition of solvency standards can be one of the ways to achieve this objective. Given the very different stages of development of insurance among RCEP members, it is understood that no effort towards standardisation or harmonisation of insurance rules and regulations is attempted at this stage.

Third, insurance demand will benefit directly (e.g. through new inbound foreign direct investment) and indirectly (e.g. through income growth and higher asset ownership) as economic growth benefits from trade deals. This will probably represent the biggest gain for insurance from RCEP. We tried to put a figure on this potential, making use of 1) estimates of economic benefits from RCEP; and 2) insurance penetration rate of individual RCEP members. Recent estimates suggested that RCEP could add to global income of USD 186 billion in 2030, under a “business as usual” scenario. Based on this scenario input, we project that insurance premiums in RCEP15 could be USD 9.6 billion higher than otherwise, in 2030.[11]

Additionally, some pockets of opportunities are arising from RCEP:

- The rules of origin under RCEP offer favourable incentives for manufacturers to set up their supply chains in Asia. This will increase the attractiveness in particular of Southeast Asia, relative to other emerging regions, as major production hubs of manufacturing goods. In turns this will foster more insurance demand related to infrastructure, manufacturing establishments and business interruption.

- The RCEP Agreement includes provisions to support the development of new financial services and payment/clearing systems, and to strengthen cooperation in e-commerce. This could help to enable new insurance business models that leverage on advance technologies, including but not limiting to online insurers, aggregators, healthcare platforms, etc.

- The commitment to national treatment and most-favoured-nation treatment in investment could encourage more foreign investments in the insurance/reinsurance sector across the region, including through M&A.

- While measures to support small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs) are mostly gearing towards rising awareness (of RCEP) and information sharing, this shows the members’ keen interest in supporting and fostering the growth of the SME sector, which is also one that is believed to be heavily under-served and under-insured.

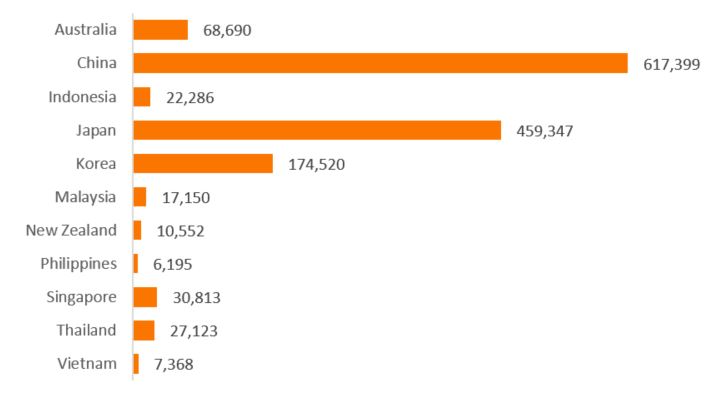

Exhibit 2: insurance premiums of RCEP15

Total premiums, USD million 2019

Source: CEIC, regulatory reports

Understanding insurance needs in the new era

In a way, RCEP will add to the growth momentum of Asia insurance and solidify the region’s role as the leading insurance region in the decades to come. However, in order to realise this potential, insurance and reinsurance players will need to better understand the insurance needs in the new, post COVID-19, era. As an example, while RCEP offers stronger incentive for manufacturers to keep and maintain their supply chain in the region, managing supply chain risk remains a daunting challenge in the face of heightening systemic risk amid ongoing geopolitical tensions. This requires the insurance and reinsurance industry to strive for innovation and better client services to meet the needs of customers. Other trends, including the proliferation of digital ecosystems, widening societal gaps, sustained low interest rates (financial repression), and the need to deal with climate change (sustainable insurance) are all important consideration for insurers working to realise the potential of RCEP.

[1] See Joint Leaders’ Statement on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/rcep/news/joint-leaders-statement-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep

[2] India has subsequently opted out of RCEP.

[3] See Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, https://rcepsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RCEP-Guiding-Principles-public-copy.pdf

[4] See Joint Leaders’ Statement on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), op. cit.

[5] Source: The Economist, Big deal – who gains from RCEP, Asia’s new trade pact, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/11/21/who-gains-from-rcep-asias-new-trade-pact

[6] The average tariff of ASEAN countries on imports from RCEP partners had already dropped from 4.9% in 2005 (10.3% non-weighted by ASEAN countries’ import shares) to 1.8% (3.2% non-weighted) currently. Source: https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/publications/specials_fmo/2020_11_17_RCEP_RulesOfOrigin.html

[7] In other words, RCEP is more supply-side focused and aimed “to tidy up the patchwork of pre-existing FTAs”. See EIU, “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Set to strengthen Asia supply chains?”, December 2020

[8] For instance in terms of labour, environment and state-owned enterprises.

[9] See: ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025, The ASEAN Secretariat, https://www.asean.org/storage/2016/03/AECBP_2025r_FINAL.pdf

[10] See RCEP Agreement, Market Access Annexes, https://rcepsec.org/legal-text/

[11] The methodology makes use of the insurance penetration of each market as well as the GDP impacts based on estimated income impact of RCEP from the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The estimate on insurance premium impact takes into consideration the direct GDP impact, but not the indirect impacts for instance through less impediment to the practice of insurance in the region. See Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer, “East Asia Decouples from the United States: Trade War, COVID-19, and East Asia’s New Trade Blocs”, June 2020, PIIE Working Paper 20-9.

with Peak Re