- Two key events in the final quarter of 2024 will dominate uncertainty in the global economic outlook: monetary easing by major central banks and the US elections.

- Recent activity data points to slowing GDP growth momentum in parts of the US economy and weak activity in Europe and China. However, the resilience of US consumer spending along with supportive monetary policies in advanced markets should provide reassuring stability to global growth.

- We discuss the impact on the global economy of the Fed's balancing act between inflation and labour markets, the policy uncertainty arising from the US presidential election, and China's recent stimulus.

Global growth is slowing but resilient

Global GDP growth remains resilient, driven by strong US household consumption and sanguine emerging market performance, particularly from Asia. However, the economic momentum is expected to soften and uncertainty to increase entering the final quarter of 2024, driven by two significant events – (i) global monetary easing by major central banks and (ii) the US elections.

Activity data across major economies are showing some signs of weakening. This includes the softening labour market and weakening manufacturing sector sentiment in the US, an ongoing industrial recession in Germany, a continued drag on growth from the property sector and anaemic consumer sentiment in China.

On the other hand, inflation in advanced economies is gradually normalising, primarily due to declining goods and commodity prices, thus allowing central banks to turn more accommodative on monetary policy. While this offers some near-term growth support, the cause and pace of the economic weakness and how it influences the disinflation path will be key to monitor.

The US Federal Reserve kick-starts monetary policy easing

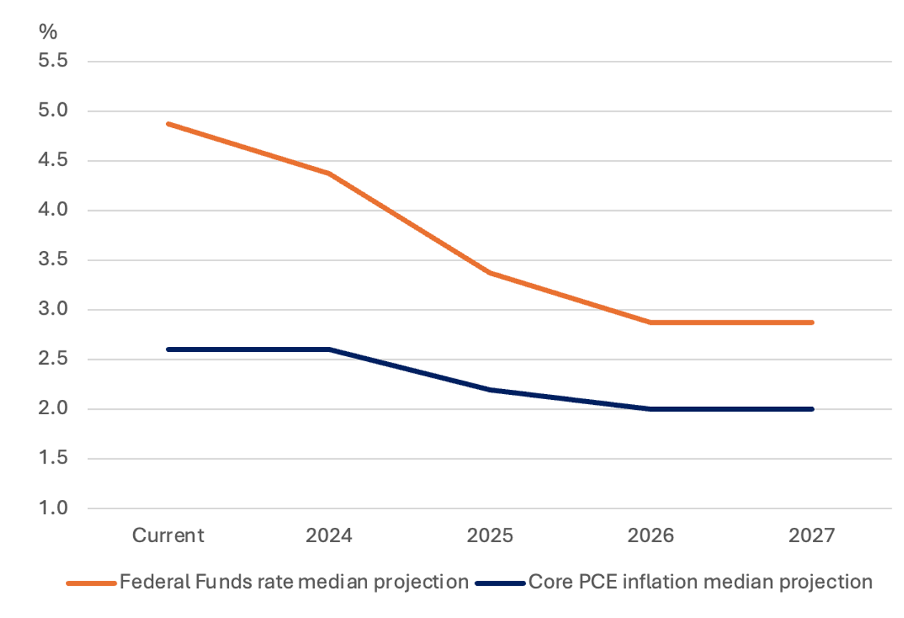

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) initiated its monetary easing cycle in early September, following the path of other major central banks, including the European Central Bank and the People’s Bank of China. The Fed nonetheless surprised expectations by delivering a larger-than-expected half-a-percentage point reduction in its policy rate and guided for another half-a-percentage point reduction by the end of 2024 (Figure 1). This marked a shift in its stance, from bringing inflation under control to a more balanced approach towards its dual mandate of price and employment stability. The US GDP growth is projected to remain steady at 2% for 2024 and 2025 [1], assuming the cooling of the labour market remains gradual.

Figure 1: US Federal Reserve projections for interest rates and inflation

Source: September 18, 2024: FOMC Projection materials

Is there an imminent threat of economic recession in the US?

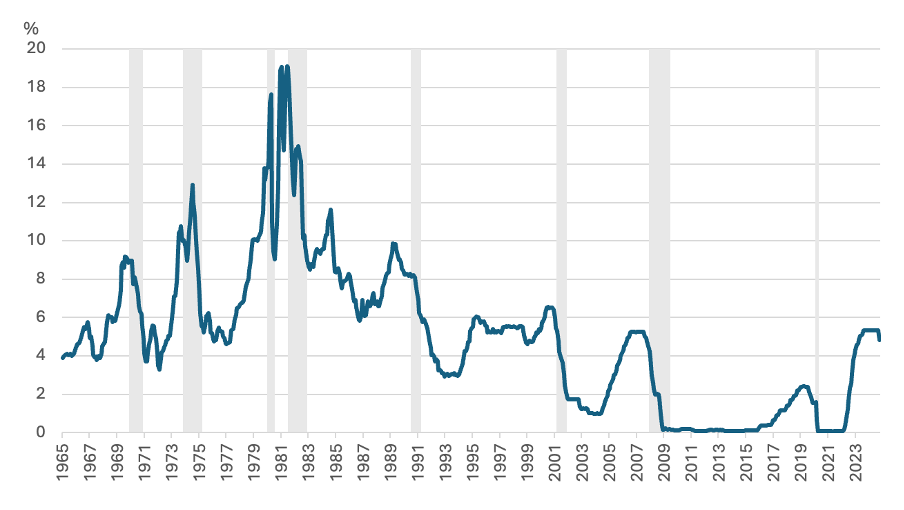

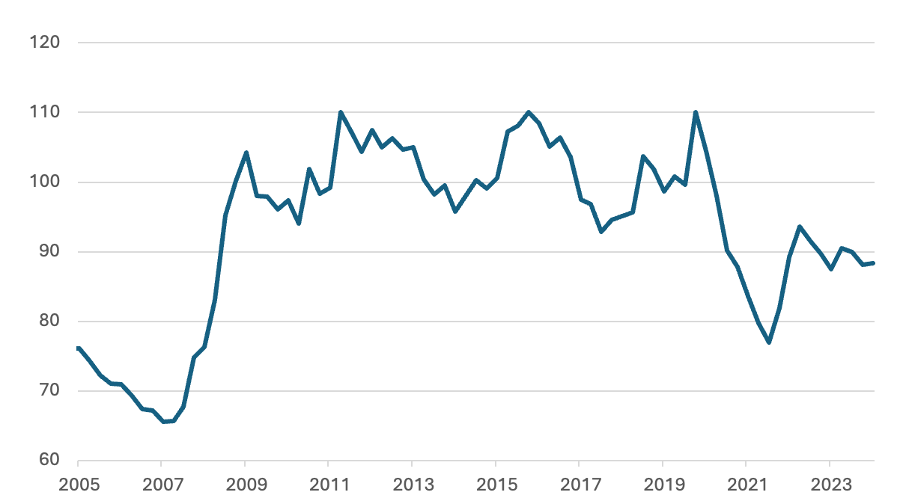

The balancing act between inflation and growth has historically been challenging for the Fed to achieve. As Figure 2 shows, the beginning of US interest rate cut cycles has often preceded US recessions. Arguably this is because periods of high interest rates have often exposed deeper economic imbalances (such as the unchecked leverage in the sub-prime housing market that preceded the 2008 crisis or the stock market exuberance of the dot-com bubble in the 2000s) or the rate cut cycles have been triggered by external shocks (such as the Gulf war in 1990 or COVID-19 pandemic in 2020)[2].

Figure 2: US Federal Reserve policy rate reductions often preceded US recessions

Source: NBER, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data

Note: Grey areas mark periods of US recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

In the current cycle, two factors have helped reduce the pain of the steep 5.25% interest rate increase - (1) The US private sector, including households, corporate and financial firms, have significantly deleveraged since the 2008 financial crisis, in part due to lessons learnt from the crisis and due to tighter regulations for financial firms, and (2) the US household and corporate sectors were able to lock-in lower interest rates on their borrowings during the pandemic era and thus less exposed to the subsequent sharp rise in interest rates. Smaller pockets of imbalances have been exposed in the collapse of three small US banks, including Silicon Valley Bank, in March 2023, and in consumer stress reflected in rising US credit card delinquencies. However, we believe these are far from major excesses that have driven prior recessions.

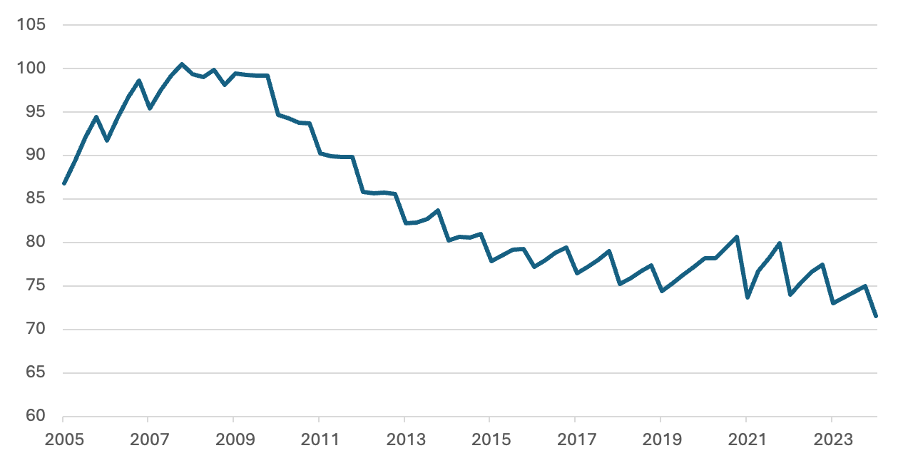

Instead, in this cycle, private sector leverage remained contained (Figures 3 and 4) while public sector borrowing has increased appreciably. Fiscal outlays to households during the pandemic contributed to an increase in household savings and supported consumer spending, while the stimulus to corporates through the Inflation Reduction Act supported private investments.

Figure 3: US non-financial corporate debt to equity ratios

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Figure 4: US household debt to GDP ratio

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Another sign that the US could avoid a hard landing is the gradual pace of adjustment in both inflation and employment. A key source of uncertainty during the turn of monetary policy cycles is the leads and lags between policy action and its effects on the economy, which makes finding the equilibrium challenging.

In the current cycle, inflation has moderated closer to the Fed’s inflation target of 2% (PCE core inflation moderated from a high of 5.575% in Feb 2022 to 2.6% in August 2024) without a substantial increase in the unemployment rate and without significantly weighing down credit and economic growth. The gradual pace of adjustment in monetary policy could support a soft landing of the US economy while avoiding a recession - barring major external shocks or significant policy surprises following the US elections.

Uncertainty around US election results

The tight race between the two US Presidential candidates and the wide divergences in their policy stances means that the US election outcome could have significant macroeconomic consequences for the US economy and beyond. For example, the divergence in the proposed corporate tax by the two candidates has implications for US growth as well as US fiscal stability. Meaningful increases in import tariffs and tighter immigration policies could create inflation and labour market shocks across the globe, while lowering the US economic output[3].

For emerging markets, the direction of US trade policy and tariffs will be key. Former President Trump has proposed a 10% universal import tariff and a 60% tariff on imports from China, affecting more than USD 3 trillion in global trade[4]. The tariffs would likely prove disruptive for export-driven economies, particularly in Asia and South America, for whom the US is a large trading partner. At the same time, a 60% import tariff on China could prove to be an opportunity for other emerging economies that have benefited from the ongoing diversification of manufacturing supply chains. The democratic candidate’s stance on trade seems to be more focused on limiting China’s access to high-tech technologies and semiconductors, which we believe has less disruptive implications for the US and the global economy.

Diverging outlook of emerging Asian economies

We discussed in our last quarterly outlook that some of the large Asian emerging markets (outside of China), such as India, the Philippines and Indonesia, are outperforming their trend growth thanks to a boost in household consumption spending and government infrastructure spending (see: Global Economic Outlook: Emerging markets stay resilient amid high global interest rates). Given the strong domestic support, we expect these economies to remain resilient to softening growth from the US, Europe and China.

Elsewhere, Vietnam and Malaysia are likely to remain the key beneficiaries of the ongoing reshoring of manufacturing supply chains, which has also been reflected in a rise in their exports, particularly to the US. Taiwan and Korea have benefited from the recent surge in technology and AI-related exports. However, we are cautious about the outlook for the tech-focused, export-oriented economies, which could be muddied by a slowdown in consumer demand from advanced markets or from shifts in trade and tariff policies following the US elections.

China's stimulus a near term support but not enough to address core challenges

Nonetheless, we believe the 2024 GDP growth target of 5% is within reach, provided timely policy actions are taken to lower the real interest rates and restore consumer confidence. A major step was taken on 24 September when Chinese regulators announced a range of policies to support the economy, including lowering the policy interest rate by 0.2 percentage points, cutting banks' reserve requirement ratio by half-a-percentage point, and reducing interest rates on existing mortgage also by around half-a-percentage point.

This will nonetheless need to be followed by more forceful fiscal policies that are proactively deployed to support the economic transition away from the traditional manufacturing and export-driven model towards domestic consumption while also planning for medium-term challenges such as ageing demographics and declining labour productivity. Reducing reliance on exports would also help increase resilience from global growth weakness and hostile trade policies.

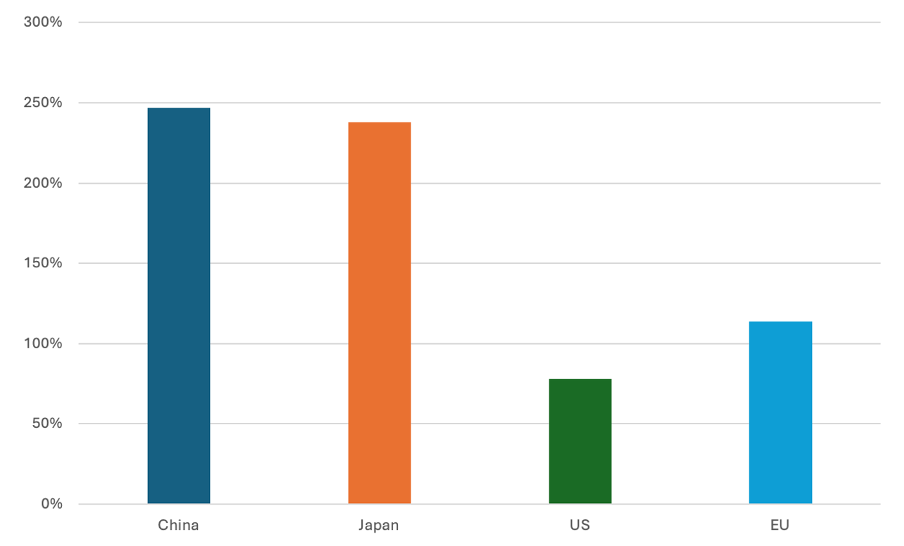

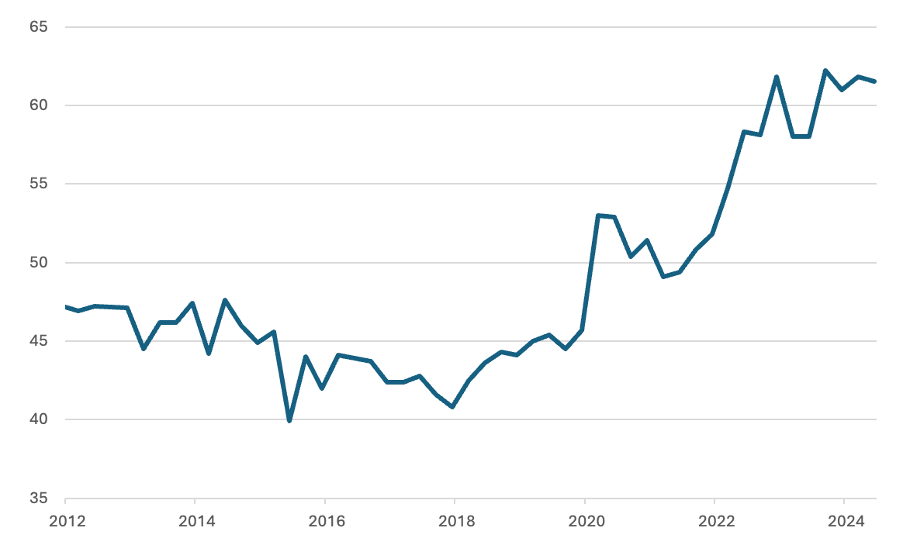

Figure 5: M2/GDP ratio

Figure 6: China Urban Depositor % Preference for Savings

Source: CEIC, PBoC Urban Depositor Survey

Global growth momentum is likely to soften but remains sanguine. The strong consumer-driven spending from the US and some large emerging markets remains constructive. Within Emerging Asia, even as China is facing significant medium-term headwinds to economic growth, there are rising opportunities for diversification within the region where domestic consumption trends are rising and economies are benefiting from a reshoring of supply chains and rising labour productivity.

[1] Federal Open Market Committee: September 18, 2024: FOMC Projection materials

[2] Journal of Economic Perspectives – Volume 37, Number 1: Landings, Soft and Hard: The Federal Reserve, 1965-2022

[3] Peterson Institute of International Economics: Can Trump replace income taxes with tariffs?, by Kimberly Clausing, Maurice Obstfeld.

[4] Intereconomics Volume 59, 2024: Trump’s 2025 Tariff Threats, by Kimberly Clausing, Maurice Obstfeld.

with Peak Re