Summary

Emerging Asian countries have demonstrated remarkable resilience in recent years, weathering the storm of the COVID-19 pandemic, global supply chain disruptions, and escalating geopolitical tensions. Despite a dip in growth to -0.5% in 2020, this was significantly less severe than other major economies or regions, a testament to their strength and potential.[1] The region bounced back strongly in 2021 and maintained steady growth in subsequent years, supported by improving domestic consumption and exports. This ability to recover quickly is partly due to the region’s greater resilience to external shocks, including global supply disruptions with robust infrastructures playing an important role.

However, the distribution of infrastructure services across emerging Asia is uneven and falls short of what is needed to sustain the region’s rapid economic growth. Moreover, the region is grappling with a growing infrastructure financing gap. Traditionally, infrastructure projects relies heavily on public finance. However, with the post-pandemic erosion of fiscal capacity and the redirection of government finance to other priority areas like healthcare and social security programs, there are increasingly concerns about governments’ financial support of infrastructure construction. This underscores the importance of private funds in bridging the infrastructure gap, which in turn depends on a number of considerations.

First, the infrastructure gap varies significantly across the emerging Asia region, with lower-income countries typically struggle to build and/or upgrade their infrastructure. Second, the pandemic has highlighted the need to invest in healthcare, social security, and disaster preparedness, leading to competition with more traditional infrastructure projects like the construction of transportation and logistics hubs. Third, there is an urgent and immediate need to invest in climate adaptation and mitigation measures (and infrastructures) against the increasing frequency and severity of extreme climate events. Fourth, by signing the Paris Agreement, countries have made a firm commitment to investing in green projects. Investment in carbon transition will represent a crucial step in reducing carbon emissions and building a sustainable future.

Demonstrated resilience against external shocks

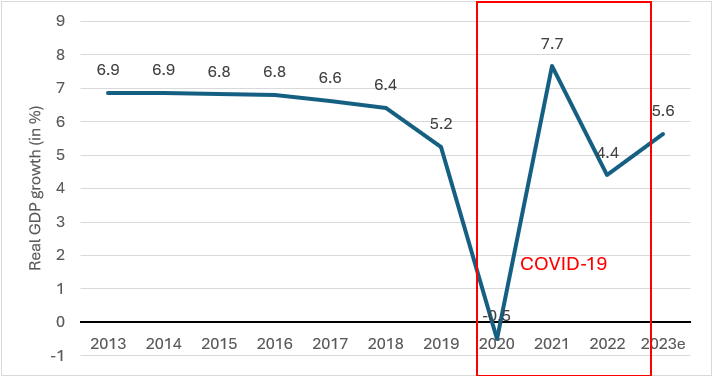

Emerging Asia economies contracted by 0.5% in 2020, the first outright recession in recent history. However, the recession was much shallower than in other major economies or regions. For instance, the US shrank -2.2% and the Euro area -6.1% in 2020. Economic growth of emerging Asia markets recovered from 2021 (see Figure 1),[2] supported by robust domestic consumption and strong exports. While the subsequent disruption to the global supply chain has had its impact felt across the globe, emerging Asia still managed to grow its exports by 4.4% per annum from 2020 to 2023, against a global average of 2.1%. This reflected the region’s adaptability despite being at the heart of the worldwide supply chain. The region’s resilient infrastructure network, including transportation systems, logistics hubs and digital infrastructure, has played an important role in ensuring the movement of goods even under challenging circumstances. This demonstrates the success of government policies in building connectivity at the national and regional levels and integrating technologies that can respond rapidly to disruptions.

Figure 1: Real GDP growth (in %) of emerging and developing Asia since 2013

Source: World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund, April 2024

Notes: e means estimate Emerging and developing Asia is composed of 30 countries including Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Fiji, India, Kiribati, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nauru, Nepal, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Samoa, Salomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Vietnam.

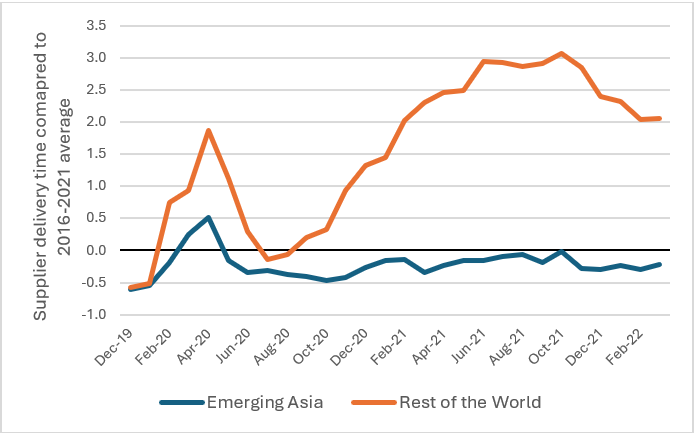

To illustrate, emerging Asia reported less delay in delivery times compared to the rest of the world (see Figure 2)[3] during the height of the pandemic and global supply chain disruptions. Deliveries from China, Indonesia, India, and Thailand were even faster on average than between 2016 and 2021. Delivery times for products from the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia were longer during the same period but still less than the corresponding increases in the Eurozone, the US, and other major advanced economies.[4] The difference in delivery time delay across emerging Asia was partly due to the uneven endowment of infrastructure. Countries with better infrastructure tend to be able to maintain or even shorten delivery times.

Figure 2: Supplier delivery times of emerging Asia and the rest of the world

Source: CEIC Data Company; and World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund, October 2021. Data points calculated by ADB

Notes: The graph shows the standard deviations between the index and the full sample mean over 2016–2021 for all economies with data. A negative data point means the delivery time is faster compared to the 2016-2020 full sample mean. Emerging Asia comprises India, Indonesia, Malaysia, China, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam weighted by gross domestic product (GDP) based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP).

Infrastructure financing gap in emerging Asia

Resilient infrastructure is indispensable to supporting emerging Asia’s economic growth and sustainable development. Yet, the region faces the challenge of insufficient infrastructure that is unevenly distributed, and existing infrastructures need to be modernised. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that emerging Asia will need to invest USD 13.8 trillion or USD 1.7 trillion annually in infrastructure from 2023 to 2030 to sustain economic growth, reduce poverty, and incorporate climate adaptation and mitigation measures. Climate adaptation and mitigation measures against natural events are particularly important for this part of the world, which is facing more frequent and intense climate events. For ASEAN, these estimations came to a total of USD 3.1 trillion or USD 210 billion annually. Traditionally, governments are responsible for a large majority of infrastructure financing (up to 92%, according to ADB).[5]

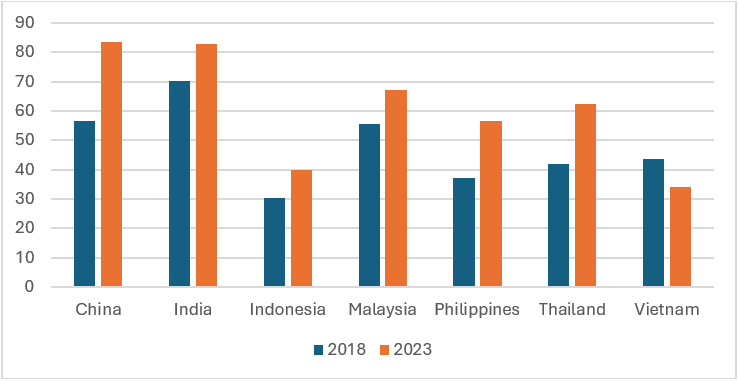

Infrastructure investment is still high on the policy agenda of governments across the region, but many governments experienced eroded fiscal capacity post-pandemic and need time to restore their finances (see Figure 3). In addition, the pandemic has pointed to the need and raised public expectations for investment in healthcare, telecommunication, energy production and transmission, and other public services that are essential to disaster preparation, response and recovery. While they are not necessarily mutually exclusive, this could still crowd out funding for some infrastructure projects in favour of other social protection and security programs. In order to fill the infrastructure financing gap, it is thus important for emerging Asian markets to tap into private funding.[6]

According to the World Bank, in 2022 and 2023, South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific attracted an average of USD 57 billion in private investment in infrastructure.[7] This is far below the ADB estimated annual requirement (USD 1.7 trillion) and is only one-fifth of the roughly USD 258 billion global private capital invested in infrastructure. Political instability, weak governance, inadequate regulatory capacity, currency risk, financing structure, and absence of a robust pipeline of viable investment projects are obstacles quoted by investors to explain the lack of interest. [8][9]

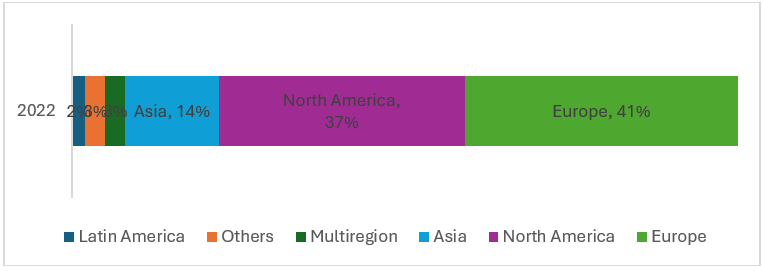

According to Global Infrastructure Hub, almost 80% of global private capital invested in infrastructure in 2022 was allocated to financing projects in North America and Europe, with a significant tilt towards green projects.[10] Asia, including emerging Asia, managed to attract only 14% of the total (see Figure 4). Recently, an increasing number of green projects has been observed in emerging Asia. As signatories of the Paris Agreement, countries are stepping up efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and invest in renewable energy and other green projects. It is hoped that the coming into pipeline of more green projects will attract a bigger share of global infrastructure capital to Asia.

Figure 3: General government gross debt as % of GDP

Source: World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund, April 2024

Figure 4: Private infrastructure capital invested by region in 2022

Source: Infrastructure Monitor 2023, Global Infrastructure Hub, 2023

Transiting to greener energy sources

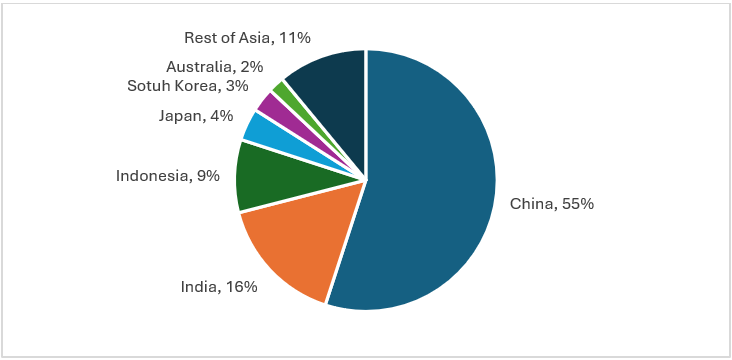

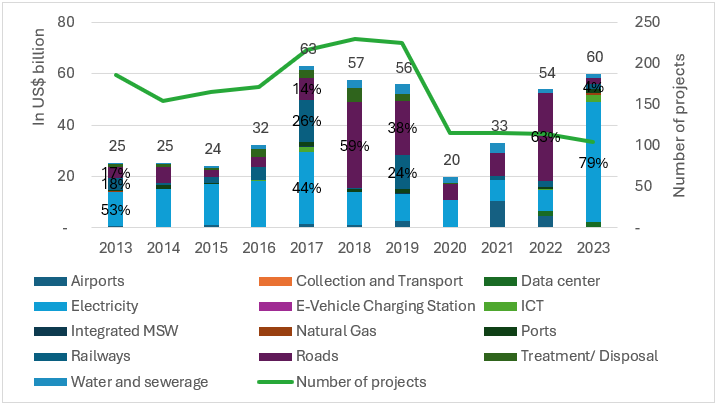

Financing energy transition will be a significant driver for infrastructure investment in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region as half of the global carbon emissions in 2022 came from APAC, and over half of this was from China (see Figure 5).[11] In addition, as the region is expected to increase digital connectivity and grow strongly in the next decade, the demand for energy will surge. In 2021, PwC expected energy demand in Southeast Asia to increase by 60% by 2040.[12] Therefore, there is an increasing interest in investing in clean and renewable energy generation (such as large-scale green hydrogen and ammonia-based systems), storage technology, transmission and distribution (see Figure 6).

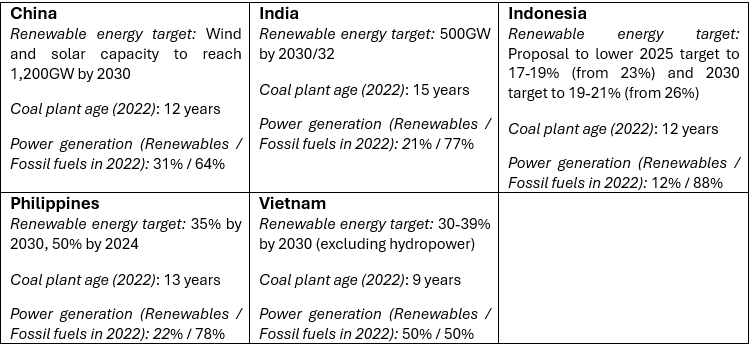

However, for most Asian countries, the transition to cleaner energy will take longer than expected. In 2022, around 70% of the electricity in the region is generated from fossil fuels, including coal-fired power plants (see Figure 7). These coal plants are generally still young, having been operating for up to 15 years. Since the economic life of coal plants is at least 25 years, it is costly to shut them down shortly. And it is still more economical to generate electricity from fossil fuels despite the rapid decline in the cost of renewables.

Nevertheless, power generation from renewables (like solar and wind) is steadily taking off. Progress is uneven across the region. In China and Indonesia, governments play a crucial role in the transition journey, while in India, the transition is shaped to a larger extent by market forces.[13] China has distinguished itself from other countries by investing heavily in renewable energy over the past decade. For instance, China added 300 GW of renewable capacity in 2023, representing half of the world’s new renewable capacity. These renewable additions comprised 51% of China’s new power capacity in 2023. S&P Global expects China to add 200 GW of renewable capacity yearly over the next two to three years.

Figure 5: Greenhouse gas emission share within Asia-Pacific in 2022

Source: Credit FAQ: How Asia-Pacific Will Pay For Its Carbon-Cutting Infrastructure, S&P Global, 2024

Figure 6: Number of private infrastructure projects and investments in South and East Asia and Pacific

Source: Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, the World Bank

Figure 7: Power generation and commitments

Source: Asia-Pacific Energy Transition: Adapting To Looming Execution Risks, S&P Global Ratings, 2024

Notes: Renewables include hydropower and exclude nuclear. Fossil fuels include coal, natural gas and oil.

Investment opportunities and insurance growth

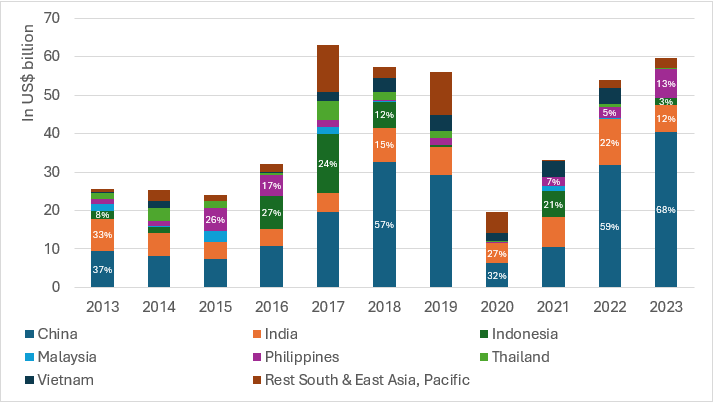

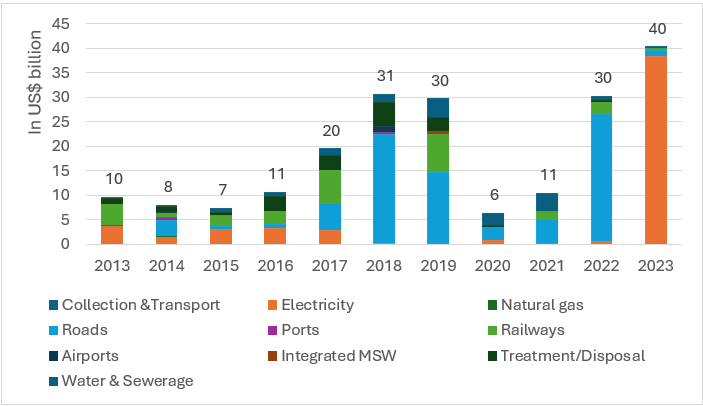

China has gained the most traction in recent years, attracting around 60% of the private infrastructure financing in emerging Asia for two consecutive years (see Figure 8). With a greater focus on energy transition, private investment funds have shifted decidedly their focus from transportation to electricity projects in 2023 (see Figure 9). Meanwhile, S&P Global expects Southeast Asia and India to catch up in the next decade.[14] India’s infrastructure spending is expected to rise by 11% in 2024. The Indonesian government has formulated a plan in 2016 to bolster infrastructure investment and incoming president Prabowo Subianto is expected to continue to support the plan. Also, some investors and manufacturers are looking to diversify sales and supply chains away from China, which could drive demand for infrastructure including energy production in many Southeast Asian countries.

Figure 8: Total private infrastructure investments in South and East Asia and the Pacific split by country

Source: Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, the World Bank

Figure 9: Privately funded infrastructure projects in China

Source: Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, Country Snapshots, the World Bank

Note: MSW means Municipal Solid Waste

It is also noteworthy that the Belt and Road Initiative led by China has had a strong positive impact on infrastructure construction projects ranging from transportation, energy to sustainable agriculture and food safety.[15] Projects including railways, highways, airports, and ports increase connectivity between cities, reducing travelling and delivery time, as in Indonesia, the Philippines, Cambodia, and Laos. At the same time, there were numerous projects that aim to improve energy production and storage capacity and target the transition to renewable energy, as in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

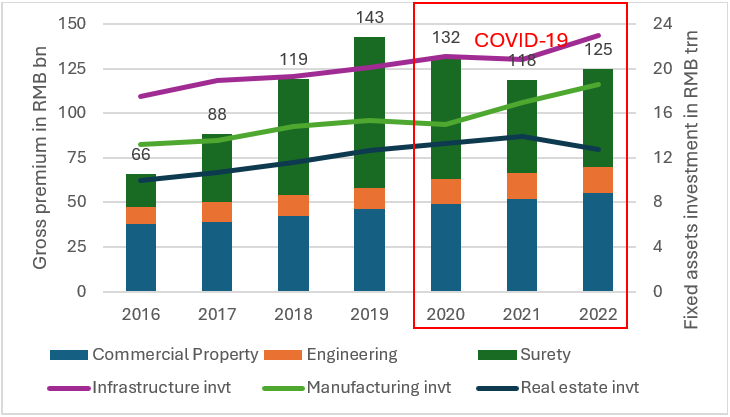

Building infrastructures have both immediate and longer-term social and economic impacts. Immediate impacts include job creation and insurance demand, particularly for engineering, marine, credit and surety, and workers’ compensation insurance during the construction phase. Commercial property and business interruptions are usually purchased during the operational phase.

As an example, although there are other drivers, the strong growth in infrastructure investment has contributed to rising demand for engineering and commercial property insurance in China (see Figure 10). In particular, surety insurance has grown sharply to become the biggest contributor to commercial insurance premiums. Premium reduction of surety insurance in 2020 and 2021 was driven by market competition lowering premium rates. Looking ahead, since real estate investment has started to trend lower from 2022, and manufacturing investment remains uncertainly given heightened geo-political tensions, it is expected that the Chinese government will be supportive of infrastructure investment to stabilize economic growth in the near future.

Figure 10: Gross premiums of selected lines of business vs fixed assets investment in China

Source: China Statistics Yearbooks (2016-2023), National Bureau of Statistics of China and Peak Re’s estimates

Notes: invt means investment. Infrastructure Investment refers to projects and facilities related to transportation, communication, public facilities, etc.

Conclusion

Emerging Asia has invested heavily in infrastructure, such as transportation and utilities, in recent years. These efforts to increase connectivity are critical in developing a resilient economy. Reduced supply chain disruptions and improved manufacturing and delivery efficacity are among the proofs of the success. The region is expected to remain the global main supplier and producer of manufacturing goods. Sustained investment in infrastructure to improve connectivity and increase energy production and storage are essential to further develop economic resilience against external shocks.

Since the 2000s, Asia has reported around a 1% default rate on infrastructure bonds, the lowest globally. Strong government support significantly contributed to controlling the low default rate level even during the pandemic. Emerging Asian governments generally intend to build more infrastructure in the coming years. This will translate into stronger demand for insurance protection like engineering, marine, credit and surety, and workers’ compensation insurance.

[1] World Economic Outlook Database, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), April 2024.

[2] World Economic Outlook Database, IMF, April 2024.

[3] Your Questions Answered: How Resilient Have Asia’s Economies Been During the Pandemic? Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2022

[4] Asia’s Resilient Supply Chains Withstand Pandemic and Global Turmoil, Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2022

[5] Reinvigorating Financing Approaches for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure in ASEAN+3, Asian Development Bank, 2023

[6] Credit FAQ: How Asia-Pacific Will Pay For Its Carbon-Cutting Infrastructure, S&P Global, 2024

[7] Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, Country Snapshots, the World Bank

[8] Reinvigorating Financing Approaches for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure in ASEAN+3, the World Bank

[9] Credit FAQ: How Asia-Pacific Will Pay For Its Carbon-Cutting Infrastructure, S&P Global, 2024

[10] Infrastructure Monitor 2023, Global Infrastructure Hub, 2023

[11] Credit FAQ: How Asia-Pacific Will Pay For Its Carbon-Cutting Infrastructure, S&P Global, 2024

[12] Energy transition readiness in Southeast Asia, PwC, 2021

[13] Asia-Pacific Energy Transition: Adapting To Looming Execution Risks, S&P Global Ratings, 2024

[14] Credit FAQ: How Asia-Pacific Will Pay For Its Carbon-Cutting Infrastructure, S&P Global, 2024

[15] List of Multilateral Cooperation Deliverables of the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, Belt and Road Portal

with Peak Re