Introduction

Since the inauguration of US President Donald Trump's second term, on-again-off-again tariffs and the threat of retaliatory ones have dominated headlines. Historically, tariffs and non-trade barriers are often framed as a defence against unfair foreign competition, promising to protect domestic jobs and industries. The Trump Administration has similarly invoked the need to protect domestic workers but also added a range of national security concerns, including illegal immigration and drugs.

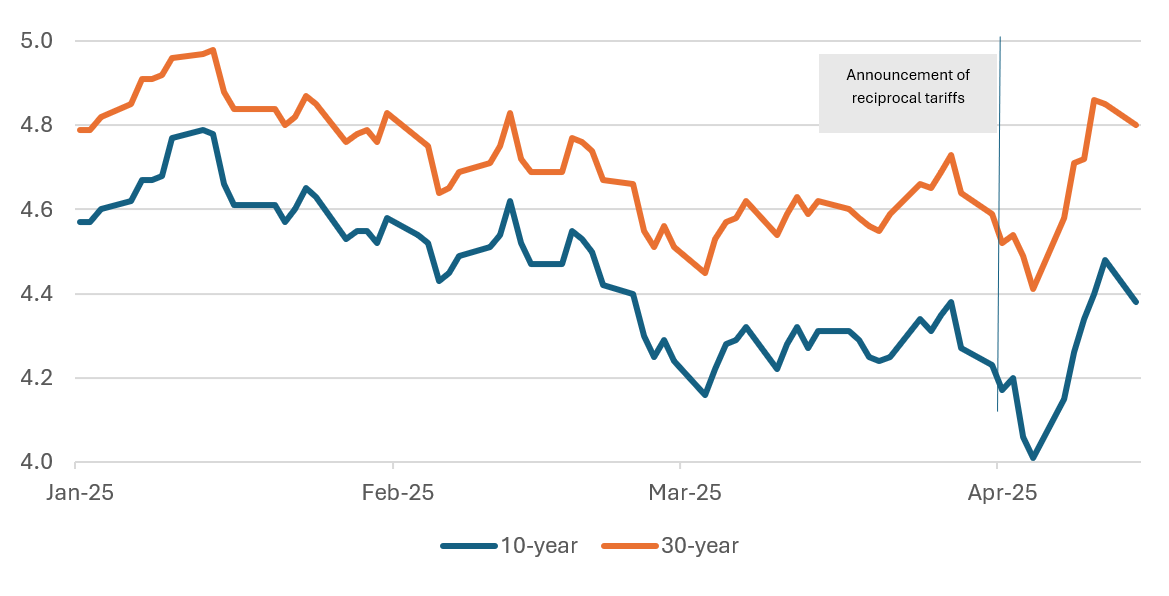

While the initial barrage of Trump tariffs targeted specific markets or sectors, including on 24 March, a 25% tariff on countries buying oil or gas from Venezuela and on 26 March, a 25% tariff on auto imports, on 3 April, the US announced a sweeping 10% reciprocal tariff on all trading partners. Higher tariffs were imposed on a long list of markets, including the EU (20%), China (54% counting the existing 20%), Japan (24%), Vietnam (46%) and other Asian markets. Indeed, Asia, particularly emerging Asia, is hard-hit by reciprocal tariffs, likely due to their larger trade surplus with the US. On 10 April, Trump paused the implementation of reciprocal tariffs for 90 days except for China (which will face a cumulative 145% US tariff).[1] It appears that while Trump has a high tolerance for stock price volatility, he is more sensitive to fluctuations in the US treasury yields (see Figure 1). In any case, there remains high uncertainty about the future path of US tariffs, especially as global reactions are still taking shape.

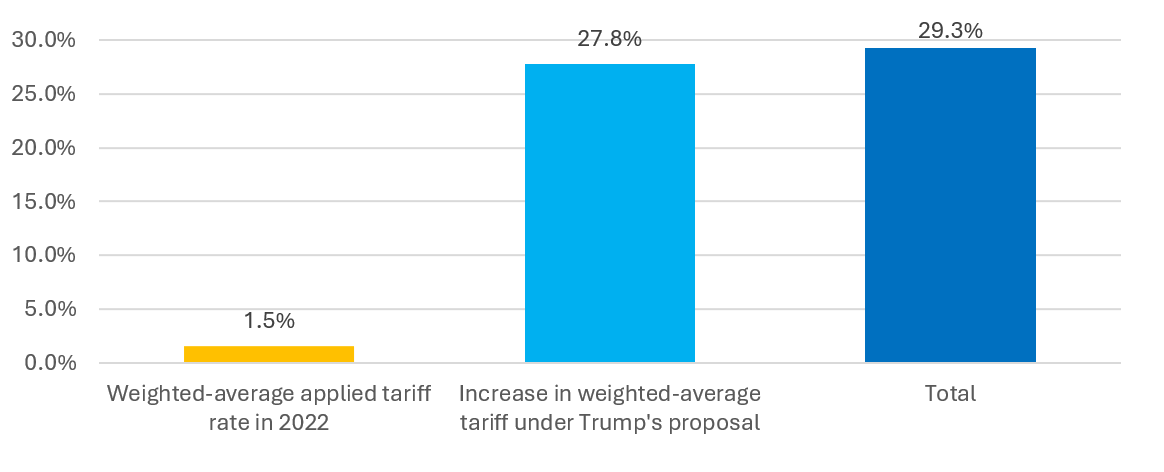

Nonetheless, the imposition of a 10% universal tariff and possible reinstatement of higher reciprocal tariffs on individual markets marks the starkest deviation from the global trade order that has existed over the last half-century (see Figure 2). The outcome is difficult to predict at this stage, but it is important to note that tariffs and retaliatory measures do not create winners — they only redistribute economic pain. This is particularly true in today's global market, where supply chains span multiple countries and continents, and productions are deeply embedded in symbiotic relationships among trading partners. International trade flow is a reflection of global specialisation based on comparative advantages as much as consumer demand.

This paper will highlight a few lessons learnt from the earlier 2018-19 trade disputes between the US and China/EU. It will then try to hypothesise some of the potential impacts on insurance based on what we know so far about US universal tariffs in 2025.

Figure 1: US treasury yields shot sharply higher post-liberation day

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Figure 2: Estimated effective US tariff rate (assuming the full extent of the reciprocal tariffs go into effect)

Source: Trump Tariffs: The Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War, Tax Foundation

1. Tariffs are a hidden tax on consumers and local producers alike

Tariffs are intended as a tax on overseas exporters, but they typically end up as a tax on local consumers, reducing their purchasing power.

US importers will pay the tariffs, which they can recoup by demanding lower prices from overseas suppliers, squeezing their own profit margin, passing through the higher cost to final customers, or any mix of these options. Anecdotal evidence from the first Trump Administration’s tariffs against China showed that it is nearly always the US consumers that paid higher prices for the affected imported goods.

- A 2019 New York Federal Reserve Bank study on the first round of the US-China trade war showed that US tariffs on Chinese goods cost US households USD 831 per year.[2]

- A 2020 study published by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) highlights that the 2018 US tariffs on China have been passed on almost entirely to US importers and consumers, although there are variations by industry.[3]

- The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) highlights that the 2018-19 tariffs had other negative impacts, including reduced exports of US manufacturers that relied on imported intermediate goods and lower margins for US exporters.[4]

2. Supply chain uncertainties and disruptions raise costs for businesses

The most significant risk to the current global economic outlook is uncertainties over the scope, depth and duration of tariffs and counter-tariffs. This is holding back investment decisions and adding to stresses on global supply chains. Companies are paralysed by the uncertainty and failing to adopt coping strategies.

Some workarounds that have been used in the past may not work anymore. For example, re-routing through a third country or the use of transhipment could now be subject to the same tariffs. Many popular destinations that have benefitted from the reshuffling of the global supply chain are now facing higher reciprocal tariffs from the US. This will reduce the incentive to relocate manufacturing production to those locations. Business could shift production to the US (costly and lengthy) or leave the US market completely (also costly). In the end, there are no good choices.

- A paper published in Empirical Economics in 2022 showed that the 2018-19 US-China trade war has negative upstream propagation impacts on third countries by dampening Chinese demand for foreign inputs.[5] This shows the impact on the worldwide supply chain can be more widespread than expected or intended.

- A NBER paper in 2020 found that trade uncertainty and tariffs resulted in significant supply chain adjustments on a firm level, with consumers and downstream industries bearing most of the tariff costs.[6]

3. Retaliation could lead to a vicious spiral

During the current spate of trade confrontations, some countries have sought reconciliation, but others are showing a tougher stance. A series of counter-tariffs bought the total against Chinese exports to the US to 145%. China has countered this with an 84% tariff on US goods (as of 10 April). Importantly, during the first US-China trade war in 2018-19, around two-third of Chinese exports to the US were subject to tariffs. Today it is 100%, both ways.

Tariffs invite retaliation, and the victims are sometimes completely unrelated industries that simply happen to rely on exports. In 2018, China significantly reduced imports of US soybeans in response to US tariffs on Chinese exports of machinery, electronics and high-tech products. This has prompted the US to dispense significant subsidies to soothe the pain of US farmers. The means to counter US tariffs have also widened in recent years, including the use of “unreliable entities list”, export restrictions (e.g. on rare earths), and targeted tariffs that focus on specific US products that are politically sensitive or have significant economic impact. Some countries could also resort to currency devaluation to remain competitive.

- An IMF blog in 2019 highlighted the impact of trade diversion due to higher US-China tariffs, with Brazilian farmers benefitting at the loss of US farmers.[7]

- While the first Trump presidency was able to collect large additional revenue from tariffs, those were almost completely used subsequently as relief payments to US farmers.[8]

4. Trade wars slow global growth, and there are no winners

Arguably, trade wars have no winners. During the US-China and US-EU trade wars in 2018-2020, the only countries that benefitted were third markets like Brazil and Vietnam, as they played the role of alternative suppliers or producers. Notably, US domestic industries have largely failed to benefit, as import prices of raw materials increase, and they are more likely to be the targets of retaliation.

Indeed, it is easier to define winners or losers in bilateral trade conflicts where alternative markets/production bases (e.g. through trade re-allocations, trade diversions or the use of connector country) are available. It is more difficult to see any winner in the case of a widespread trade war with universal and reciprocal tariffs imposed on all (or most) US trade partners and policy uncertainties remaining elevated. Even if some industries (e.g. steel) could benefit from tariffs in the short term, downstream manufacturers (e.g. machinery and car producers) would pay the price.

- The World Bank projected that a 10-percentage-point increase in USD tariffs on all trading partners, and factoring in proportional retaliatory tariffs, could lower global economic growth by 0.3 percentage points in 2025.[9]

The shock wave to insurance

Given that the reciprocal tariffs were only announced on 2 April, and a 90-day pause was introduced on 10 April, it is still too early to fully comprehend the impact of the tariff on the global insurance and reinsurance industry. Nevertheless, as “failing to plan is planning to fail”, it pays to prepare for different eventuality, including one where the trade war persists and covers more large trading nations.

At this stage, it is possible that there are three broad channels where impacts can be felt.[10] First, tariffs will directly impact the value and volume of goods traded. Second, we maintain that higher tariffs will lead to slower economic growth, higher consumer price inflation and the adoption of mitigation measures (e.g. moving production to those with the lowest 10% tariffs). In that case, these macroeconomic developments will filter through to impact insurance demand. Third, trade in services, including cross-border re/insurance, is so far not affected by tariffs or countermeasures. However, if the trade war escalates, there might come a stage when services (e.g. digital advertising as in the case of EU) will come into scope.

Insurance and reinsurance will also be affected on the investment side, but this paper will not discuss this as it relates to the individual investment strategy and portfolio composition of different re/insurers. Readers can refer to the S&P report on this, which believes that the conservative investment strategies of reinsurers should mitigate significant negative impacts in the short-term. Longer-term, there are risks arising from potential asset impairments and illiquid holdings.[11]

A. Direct impact on insurance business lines

Marine cargo/trade insurance: Given that US importers are responsible for paying the higher tariffs/duties to US Customs, there are scenarios depending on the sharing of the burden among exporters, importers and consumers.

1. In the extreme case where the exporter (or overseas manufacturer) absorbs all the additional tariffs, the price of goods shipped to the US will be lowered by the equivalent tariffs, such that the total cost of the US importer (payments to the overseas seller plus tariff payments) remains unchanged. In this case, the invoiced value of exports to the US will decline, hinting at lower marine cargo insurance premiums.

2. On the other extreme is that the tariffs are absorbed completely by US the US importer (who might pass on further some of the cost to final consumers), the price of goods (invoiced value) shipped to the US will remain unchanged. In this case, marine insurance premiums will likely remain unchanged.

The impact could be somewhere between these two scenarios, but premiums will likely decline. Furthermore, total premiums could drop further because of the reduction in overall trade volume (due to higher retail prices and economic slowdown, see below). It should be noted that while previous trade conflicts have only a marginal impact on global trade (around -0.4% to -0.8% for the 2018-2020 trade war), this round of universal tariffs could potentially have a more severe impact. Given that the US has a share of 10.8% in global trade (2023)[12] and the average tariff rate (assuming full implementation of reciprocal tariffs) rising to close to 30% from 1.5%[13], the impact on global trade could be a 2% reduction.[14]

Credit insurance: It is not expected that demand for export credit insurance will be significantly disrupted until the indirect impact (see below) kicks in when weakening economic growth leads to more corporate delinquency. While the global supply chain could be disrupted by higher US tariffs, the impact will likely be mild (a change in relative price), for example, compared to COVID-induced disruptions (a sharp supply shock). Nonetheless, it was mentioned that US importers would find themselves facing a capital squeeze if the value of import duty increases sharply in the short term. Furthermore, premiums may go up slightly due to higher inflation boosting the sum insured, as was observed during the pandemic period.

Motor and property insurance: Business lines that are dependent on imports could be affected. For example, motor insurance claims could increase due to higher prices on imported cars, parts, and materials for repairs, like how inflation in 2021–2022 drove up claims for motor insurers.[15] Similarly, to the extent building materials (e.g., lumber and steel) are imported, claims inflation of property insurance could be affected. As P&C insurers can reprice their products annually to protect their profitability, some or most of the higher claim costs could be passed on to consumers. Premiums, on the other hand, could increase slower or even drop if the US, and by extension the global economy, slips into a recession due to escalating trade conflicts.

B. Indirect impact of US universal tariffs

Most economic models suggest a modest reduction in global economic growth in 2025, at a range of 0.1% to 0.3%, with the US (indeed US households) bearing most of the burden as a result of higher tariffs. While it is still too early for us to be confident in any projection on the scale of negative economic impacts, anecdotal evidence strongly suggests tariffs, if persist, will slow economic growth.[16] Trade-dependent markets like Hong Kong and Singapore will be significantly affected, irrespective of their tariff rates charged by the US.[17]

Slowing or reduced economic growth will negatively impact P&C insurance, mostly due to delays in investment decisions and weaker consumer spending and business sentiments. However, some of these could be recouped in case tariffs end or are rescinded. In the past, insurance demand benefited from the relocation of manufacturing to non-tariffed locations. However, this is becoming harder, given that most of Southeast Asia is hit with very high tariffs.

|

Premiums growth during COVID-19 A recent example helps to illustrate. In 2020, global real GDP dropped 3.7% due to the COVID-19 crisis. Global total premiums dropped 1.3%. However, most of the decline was recorded in the life sector (-4.4%), while P&C premiums grew 1.5%. This was due to strong rate hardening in commercial lines, mostly in advanced markets. Some Asian markets, including South Korea and China, reported strong P&C premiums growth despite economic hardship. |

To the extent that tariffs, as an indirect tax, raise inflation rates and inflation expectations, it will have a widespread impact on insurance. This ranges from higher operational costs to claims inflation (mostly due to higher import inflation). Meanwhile, insurance investment could benefit from higher-than-otherwise interest rates.

C. Focuses on services and non-trade barriers

The current spate of tariffs and counter-tariffs is focusing on trade in goods, but signs are emerging that trade in services, including insurance, could be targeted. The EU is mulling retaliation by targeting the US services exports, mainly digital services and technology like a tax on digital advertising which are dominated by US BigTech companies. While it is important to note that non-trade barriers in services trade are equivalent to tariffs in merchandise trade, it is still too early to speculate the potential impact on insurance and reinsurance at this stage.

Conclusion: There Are No Winners in a Trade War

“Historically, there is no winner in a tit-for-tat trade war."

There are other imminent issues that need close monitoring. As shown in previous economic crisis (for instance, the Asia Financial Crisis and the Global Financial Crisis etc), one crisis leads to another. For instance, we should be wary of the risk that a trade crisis would lead to an economic crisis triggered by a debt implosion of emerging markets, as many of them are highly in debt and rely heavily on exports to the US.

In sum, the US reciprocal tariff, despite the 90-day pause, is likely to keep market uncertainty high, raising the risk of inflation and economic recession. If these tariffs persist, they could force a fundamental restructuring of the global supply chain. The potential negative impacts include higher consumer prices, reduced corporate profit margins, and slower economic growth. However, there remains a possibility for a negotiated end to these tariffs, which could alleviate these pressures and restore stability to global trade. With ongoing negotiations, there is hope that a mutually beneficial resolution can be reached, fostering a more predictable and prosperous economic environment for all parties involved.

[1] That includes 20% on China shortly after Trump took office and 125% of reciprocal tariffs. For more details on US-China trade war tariffs, please refer to US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart | PIIE

[2] NY Fed finds new China tariffs to cost US households $100bn a year

[8] 92 Percent of Trump’s China Tariff Proceeds Has Gone to Bail Out Angry Farmers | Council on Foreign Relations

[10] The discussion on impacts on re/insurance is based on the assumption that negotiation during the 90-days pause will not yield comprehensive trade agreements that significantly reduce US-China tariffs or the 10% universal tariff. Some reinstatement of reciprocal tariffs on major trading nations are assumed.

[11] Reinsurers to weather tariff-induced market volatility with minimal impact: S&P - Reinsurance News

[12] The figure refer to merchandise imports and exports and exclude trade in commercial services. Source: WTO STATS.

[13] Weighted-average tariff rate sourced from Tax Foundation.

[14] A recent blog from the WTO suggests a decline by 1.5% in 2025. See WTO Blog | Global trade faces setback amid rising tariffs.

[15] The American Property Casualty Insurance Association expected US motor premiums to increase within 12-18 months and that costs of car repairs could go up by USD30 to 60 billion a year due to the reciprocal tariffs. Source: Car Insurance premiums will likely rise due to tariffs, industry group say, San Francisco Chronicle Web Edition, 5 April 2025.

[16] There are justifiable doubts on the possibility of successful negotiation within the 90-day pause. First, it is not at all clear about the US objectives. Second, bilateral negotiation is highly inefficient, and everyone will be benchmarking against other bilateral deals with the US. Third, the sheer number of bilateral negotiations to go through is challenging by itself.

[17] Both Hong Kong and Singapore do not have any tariffs on US imports, but are facing 10% and higher reciprocal tariffs in the case of Hong Kong.

with Peak Re